[en/nl]

The sculptures of Theo Konijnenburg invite speculation. That is a good thing, because it means there is work to be done. At least, that’s how it works for me—not to define or categorize, but to question, without filling in the “aura” of the work itself. The strength of an artwork also lies in its inexplicability. At least, that’s how it works for me, as a lover of the subliminal.

One might say there is not much left to tell, and yet, here is an attempt.

Proportion

In Theo’s work, proportions play a central role. His sculptures are often presented, per subject, not only in different materials but also in varying scales. Within his installations, a crucial focus is the way the works relate to one another and to the exhibition space. Konijnenburg determines the arrangement and dimensions of his three-dimensional works in an associative manner.

The exhibition space of Atelier 21, itself a listed national monument, already carries an inherent dynamism and character, in contrast with the more neutral atmosphere of a museum. According to Theo, however, the so-called “white cube” does not exist. He puts it this way: “There is always something you can relate to, even in a white cube. Even if it’s just a socket or some other detail in the space.”

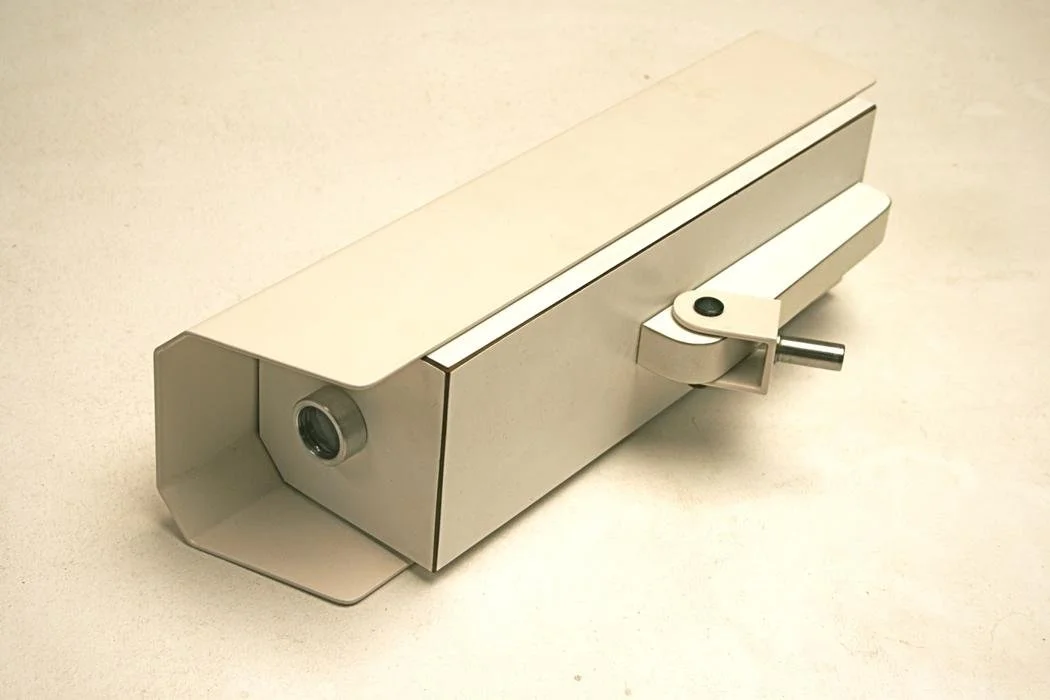

During the exhibition here, his iconic record player (a work that has evolved into a signature piece within his oeuvre) will also be on view, this time in an entirely new form.

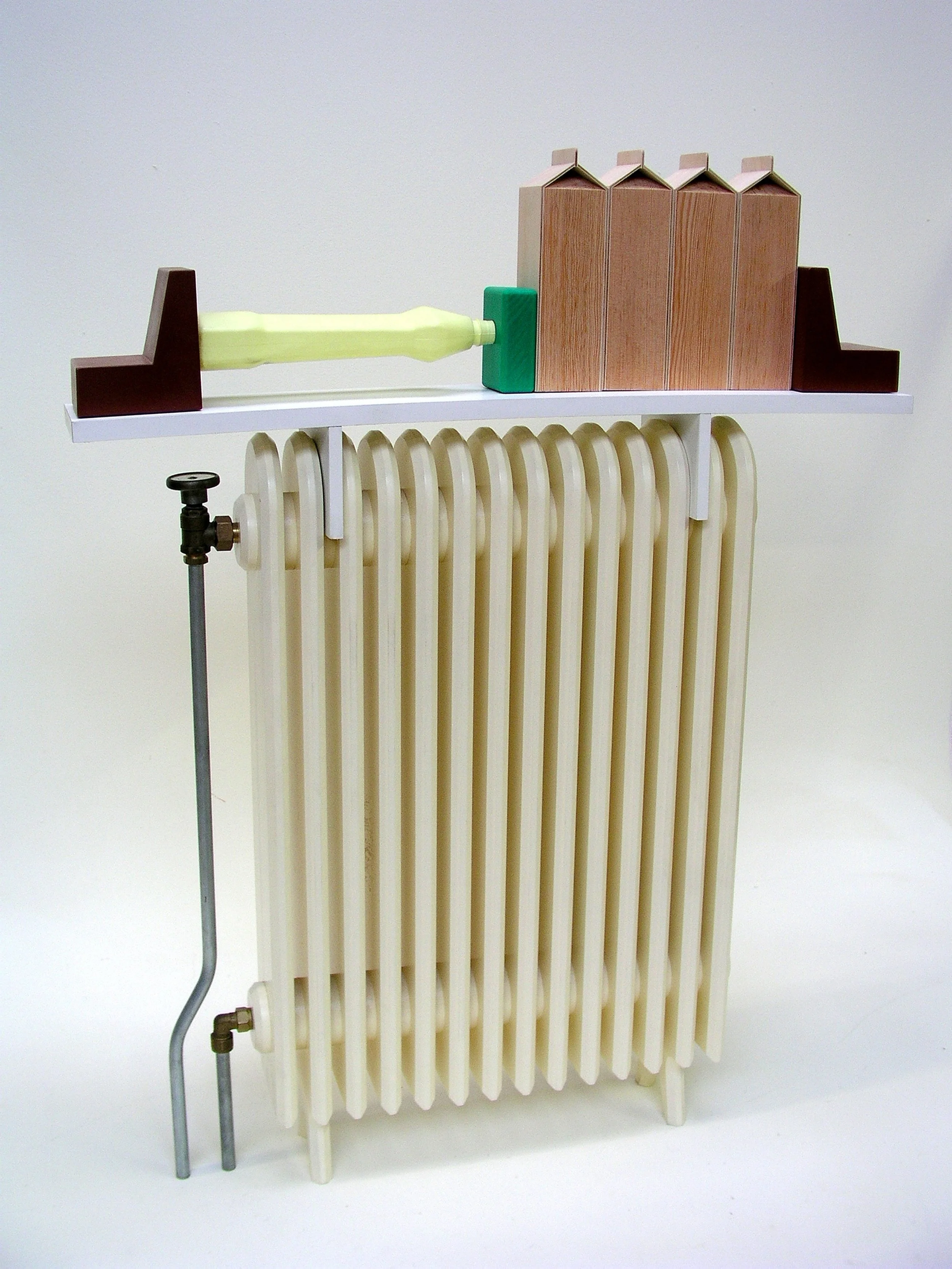

Apparent functionality

Another recurring element in Theo’s work is functionality; his sculptures seem usable but are not. DE.GROEN collection (Arnhem), which holds his work, described it as follows: “With every object he creates, he takes away the original functionality of that particular object. You cannot sit on his chair. His radiator does not produce heat. His record player does not play records.”

Building on this, one could say: he extracts an object from its ordinary function by reproducing only its outer appearance—its surface, its aesthetic design. Often, too, in a different material, so that the original mass-produced industrial product gains a redefinition: the copy undergoes a transformation by losing its functionality. The object’s initial purpose becomes useless, and the reproduction manifests itself as an autonomous artwork—a unique, handmade piece. This stands in contrast with the almost invisible presence of the mass product.

For Theo himself, however, these objects are not invisible. Because of their very general and familiar appearance, they serve as visual memories (and thereby autobiographical works) tied to his early childhood or more recent experiences, translated into form and design.

From readymade to new aura

Two names that come to mind in relation to Theo Konijnenburg’s work are artist Marcel Duchamp and philosopher Walter Benjamin. Both offered a new perspective on art in the twentieth century.

Duchamp (1887–1968) introduced the concept of the readymade in the early twentieth century: everyday objects that, through the artist’s choice and context, were declared art. His most famous readymades are Fountain (a porcelain urinal) and Bicycle Wheel (a bicycle wheel on a stool). Like Duchamp, Konijnenburg removes recognizable objects from their original context, but he not only transforms them into autonomous sculptures—he also grants them new meaning: reproduction as an artistic act.

In his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935), Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) describes how modern technologies such as photography and film allow for the endless duplication of art. As a result, he argues, the artwork loses its unique “aura”: the special presence in time and space that distinguishes the original from the copy. Konijnenburg reverses this process. He deliberately selects the mass-produced industrial object, the thing that according to Benjamin is aura-less, and reshapes it. By stripping away its functionality and presenting it as a sculpture, Theo bestows upon it a new uniqueness and visibility.

Art is the art of preventing it from becoming art

What art is seems an increasingly difficult question to answer in a world where almost anything can be art. The paradoxical statement “art is the art of preventing it from becoming art” invites us to rethink its meaning. Does contemporary art arise precisely when it resists the label of ‘art’? As a form of expression that cannot be pinned down, named, or institutionalized? Perhaps therein lies a new perspective: that contemporary art refuses to be captured, always slipping away from us.

EXPO 02.10.25 > 25.10.25

Thur-Fri-Sat 13:00/17:00 hrs

INVITATION

With the finissage of this exhibition on Saturday, October 25, we will also conclude the past season.

You are warmly welcome between 1:00 and 5:00 p.m. for a drink and some in-house culinary treats.

Theo Konijnenburg (1966) grew up in Zierikzee and left home at the age of 17. He still visits Schouwen-Duiveland regularly to see family, and now he returns to Zierikzee for the entire month of October with an exhibition, closing the season at Atelier 21 with his three-dimensional works.

Konijnenburg lives and works in Arnhem, where alongside his artistic practice he is affiliated with ArtEZ University of the Arts as a lecturer in Product Design.

BIO

images ©Theo Konijnenburg

text & photography atl21, Frans Blanker